This November, Portland Japanese Garden is proud to present, “Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga: Changing Tastes in Japanese Woodblock Prints,” a new exhibition in the Garden’s Pavilion Gallery showcasing one of the most tumultuous periods of Japanese print production through a look at the dramatic kabuki prints of Toyohara Kunichika and the immersive landscapes of Kawase Hasui. Each print in the show comes from the collection of Irwin Lavenberg, a local Portland resident who has been collecting Japanese prints for over 20 years. His acquisitions have made his collection one of the most diverse and extensive private collections in the United States.

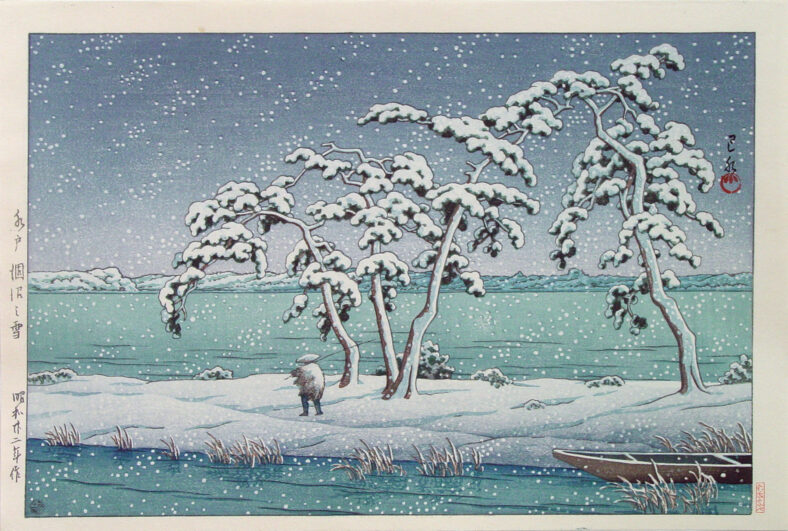

Irwin’s interest in the art of printmaking extends farther back than his knowledge of Japanese culture. Right out of college, he fell into a job as an apprentice pressman where he learned the basics of the trade – the inks, the papers and the transfer processes. He reminisces how his one-year apprenticeship was like a condensed version of the many-year apprenticeship that skilled craftsmen go through in Japan to produce woodblock prints. Returning to school for an electronics degree, Irwin moved on to work in research and development for Sony Corporation, a job requiring regular trips to Tokyo. It wasn’t long before he began venturing beyond Sony’s labs to discover more of Japan. Immersing himself in the rich culture and history of the country led him to better understand his business relationships and deepened his appreciation of the Japanese arts. Yet, it was closer to home, at an exhibition of woodblock prints by the famous ukiyo-e artists Hiroshige and Hokusai at the San Francisco Asian Art Museum, that opened his eyes to the possibility of owning Japanese art. Not long after seeing this exhibition, Irwin purchased his first woodblock print at a San Francisco gallery, titled “Snow at Hi Marsh, Mito” (1947) by Kawase Hasui, on display in this current exhibition.

Recalling the moment he first saw this print, he describes how it took him back to the end of his college days in upstate New York and to a recurring dream in which “I am standing alone, gazing into a desolate dream-like snow scene, not knowing which way my life is going to turn, but embraced by the snow and the silence.” Twenty-three years after purchasing this first print, Irwin’s collection has grown to over 2,500 Japanese prints which span a period of over 100 years.

That defining background in understanding the intricacies of the printmaking process gave Irwin another motivation behind collecting. He shares, “Sometimes, I think that I am running a ‘print pound’ or ‘emergency room’ for prints, taking in prints in poor condition and at least stabilizing them and preventing further damage.” He goes on to describe how initially in Japan, woodblock prints were not considered fine art. They were popular, mass-produced forms of advertising: promoting the offerings of big-city entertainment districts and encouraging travel to see the natural and man-made wonders of Japan.

Woodblock prints also provided the public with entertaining stories based on history and legend, even going so far as to illustrate current events as Japan emerged as a modern nation. They were collectibles, akin to baseball trading cards in the U.S., cheap to produce and purchase within the major printing centers of Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka. People would purchase prints and assemble them into albums or attach them onto backings for display. Many of the older woodblock prints that one can find today were handled frequently, and one can imagine friends sharing their latest prints or perhaps even trading them amongst themselves. While Irwin recognizes how sad it is to see prints in states of deterioration, he also sees it as evidence of how the print shared a life with a real person over 100 years ago. Tea or food stains, the signs of wear and tear, are like clues to a mystery of the prints previous owners, demonstrating how the prints were an integral part of their lives. On display in the Pavilion Gallery is one such piece that we encourage visitors to seek out and imagine its earlier life.

When asked what continues to motivate his collecting, Irwin explains that it is the “…hunt for a deeper understanding of the artist and what the artist is depicting, within the context of the time.” This quest for information inspired the creation of Irwin’s website, myjapanesehanga.com, which has become famous among Japanese art enthusiasts for the detailed and scholarly information it provides for the prints in his collection. He recalls how friends and experts in Japanese art helped him translate the text on prints, offering historical information to help him better understand the composition and stories behind the images. The impetus for My Japanese Hanga was to give back to a community that had freely provided him with so much information. Irwin wanted to amalgamate all those sources so people interested in learning more about Japanese prints could have an easily accessible resource. Going forward, Irwin is working to ensure the continuity of the actual prints after his lifetime and has made donations from his collection to the Portland Art Museum and, most recently, to the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon.

“Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga: Changing Tastes in Japanese Woodblock Prints” is uniquely curated to shed light on Japan’s seismic cultural shift in the face of rapid modernization. Irwin shares, “for this particular show, being able to present a small piece of the larger story representing ukiyo-e’s demise at a time of great societal change and transition is an intriguing challenge.” He points to how Western inventions like photography and lithography began to cut into the market for woodblock prints. As the public embraced these modern technologies, a younger generation began to see woodblock prints as old-fashioned. Kabuki actors, who had once helped subsidize the cost of woodblock print production to promote their performances, were instead giving out daguerreotypes, a form of early photographic prints.

By the end of the nineteenth century the woodblock print market was near death. For this 300-year-old art to survive, a dramatic shift had to occur—from a mass-produced product geared to a domestic market, to a fine art object, appealing to the growing foreign demand for Japanese art. Using exemplar artists like Toyohara Kunichika and Kawase Hasui, whose work represents a bridge between two great movements in Japanese woodblock prints, ukiyo-e and shin hanga, this exhibition is an opportunity to go on a mental journey, becoming immersed in another place and time. Irwin reflects, “When I come to Portland Japanese Garden, it’s a chance to think. It’s a different venue, not a museum or gallery, but one of the finest Japanese Gardens in the world that encapsulates ingenuity in not only landscape design but also architecture, and of course, countless forms of art. The resonance between the manicured landscape outside and the pieces inside the Pavilion provides a great opportunity for reflection.”

He acknowledges that, “the arts bring people together,” and hopes that the woodblock prints on display both provide a brief mental escape, while helping us experience how art can resonate with each individual, even when that art is not from our home culture.

“Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga: Changing Tastes in Japanese Woodblock Prints” will be on view in the Pavilion Gallery from November 20, 2021 – January 20, 2022.

To learn more about the Irwin Lavenberg Collection, visit his website: myjapanesehanga.com.

Exhibition Consultant: Lynn Katsumoto