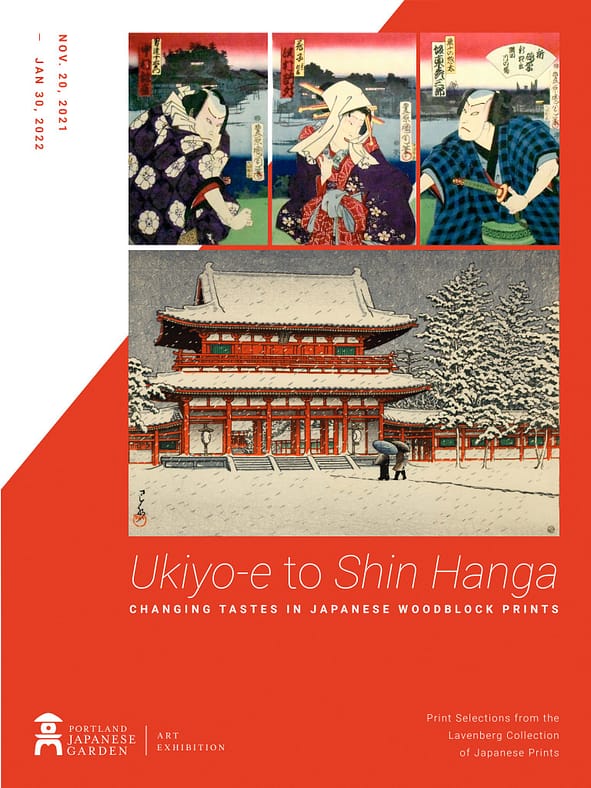

At the heart of “Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga: Changing Tastes in Japanese Woodblock Prints” are two artists, born about fifty years apart. One, renowned as a dynamo of strong, multicolor theater scenes; the other, beloved at home and abroad for subdued landscapes, rich in quietude. Between them lies the transformation of Japan as it shifted from a rigid, restrictive society ruled by a shogun to a modern nation eager to participate in the wider world.

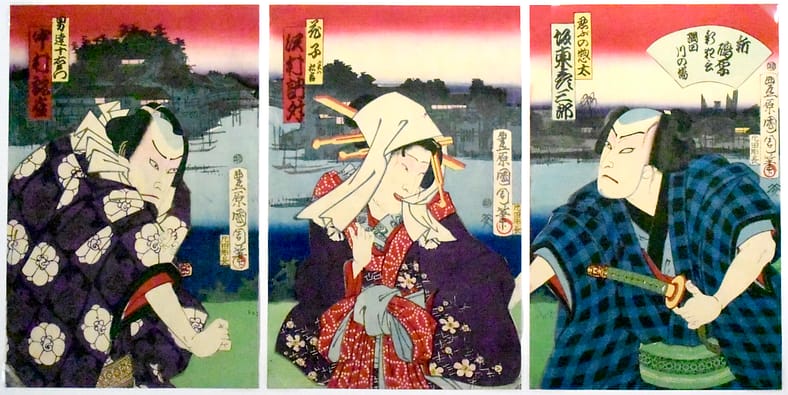

Toyohara Kunichika 豊原国周 (1835-1900)

During Kunichika’s day, woodblock prints were produced and sold by publishers who chose the subject matter based on anticipated sales, similar to how graphic designers work on assignment today. The graphics were not left to the designer’s whim; however, Kunichika’s style was sought after for his yakusha-e (actor-prints) of the kabuki stage. He adeptly incorporated imported German aniline pigments, matching their saturated colors with flamboyant kabuki scenes while also expressing the verve of the changing times. Japan in the 1860s had already opened treaty ports to Western traders. In 1868, the Meiji emperor ushered Japan into a new, modern age. As Edo became Tokyo, bright colors were seen as symbols of progress and enlightened times.

Son of a bathhouse operator in the Kyobashi area of Edo, modern-day Tokyo, the boy who became Kunichika (birth name: Yasohachi) was street-smart with a flair for painting. At around age twelve, he became a student of classical painting artist, Toyohara Chikanobu, while also producing stylized portraits of kabuki actors. Local makers of fabric pictures, lamps and other products put his artistic talent to use decorating their goods with popular art. At age thirteen, he entered the studio of the preeminent ukiyo-e designer, Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865), combining these two mentors’ names to create his professional art name, Kunichika.

Kunichika was repeatedly ranked among the top ukiyo-e artists, and in 1867 he received an official commission for his work to be exhibited in the Paris International Exposition. Fame was not a concern of his, however; a bohemian at heart, it was the theater that captivated him. A contemporary remarked, “print designing, theater and drinking were his life and for him that was enough.” A habitué of the backstage, Kunichika became close to the leading kabuki star of the day, Ichikawa Danjūrō IX, who infused the theater with a new dynamism and dramatic style during the 1880s and 90s. In many ways, Kunichika functioned as publicist to the stars, creating panoramic – even cinematic – compositions that kept them in the public eye.

By the time of Kunichika’s death in 1900, the ukiyo-e tradition was in decline, challenged by the rapid inroads of photography, photoengraving and color lithography. Well aware of the public’s enchantment with the modern and demand for the new, Kunichika strove to keep the 300-year-old woodblock tradition alive and popular with his dynamic and colorful designs, capturing the stylized bravado of kabuki as torrents of change swept across Japan.

Kawase Hasui 川瀬巴水 (1883-1957)

One of ten children in the Kawase family, the artist who became Hasui (birth name: Bunjirō) grew up in Tokyo’s Shiba Ward, present-day Shinbashi. Here, Japan’s first railroad terminals coexisted with geisha establishments, small businesses, and the beginnings of industry, making it a crossroads of old and new Japan. In this milieu, where learning to adapt was a prerequisite, Bunjirō was struck with childhood illnesses that left him near-sighted and in delicate health. Childhood trips to the hot-spring resort of Shiobara helped restore his health and likewise fostered his love of the Japanese landscape with its seasonal transformations.

Building on a fondness of drawing and copying ukiyo-e, he began formally studying art at age fourteen, learning both Japanese brush painting and Western art techniques. Circumstances, however, cut this training short and required him to manage the family silk braid business. In 1908, when he was in his mid-twenties, a relative took over the business leaving him free to recommit to art. He studied under Western-style painters, but ultimately found oil painting unsatisfying. Instead, he resumed his practice of nihonga, Japanese-style painting with mineral pigments. Two years later, the famous nihongapainter Kaburaki Kiyokata (1878-1972) accepted him as a pupil and gave him his art name, Hasui. Commercial work helped Hasui make a living, while occasional exhibitions with fellow pupils provided the public exposure through which Watanabe Shōzaburō discovered him.

Watanabe was a business-savvy, English-speaking print dealer and publisher, whose firm sold woodblock print reproductions of ukiyo-e, often to North American and European buyers. Aware of strong foreign interest in these prints, and noting ukiyo-e’s decline, Watanabe conceived of producing entirely new (shin in Japanese) prints (hanga), based on designs by contemporary artists. He sought out master craftsmen in the interest of revitalizing the traditional printmaking collaboration between artist, block carver, printer and publisher. Watanabe insisted on the highest quality materials and had an eye for finding the right type of artist to produce work that would be marketed as fine art editions to a largely foreign audience. Hasui’s landscape paintings, with their emotive blend of realism and the ethereal, struck Watanabe as adroitly combining Japanese themes with Western-inflected representation, precisely the modern look he envisioned for shin hanga.

From 1918 until the end of his life, Hasui produced over 600 designs for prints, traveling the country in search of places that retained the character and appearance of the Japan he knew as a child. He sketched outdoors, mostly with pencil, later adding colors and effects when back in his lodgings. In his own words:

“I found that the very landscapes started looking like prints to me. I do not paint subjective impressions. My work is based on reality…I cannot falsify…(but) I can simplify…I make mental impressions of the light and color at the time of sketching. While coloring the sketch, I am already imagining the effects in a woodblock print.”

The effects he was after called for new, subtler efforts from carvers and printers with whom he worked closely, advancing the art and craft of printmaking. After the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake that ravaged Tokyo, and again after the 1945 firebombing, Hasui endured losing his house, sketchbooks, and previously carved blocks. Yet, he continued his sketch trips in pursuit of time past, striving to capture an intangible essence of Japan.

Traditional, agrarian, and remote, this is the Japan that Hasui enshrined through the artistry of his prints, and what keeps captivating the hearts and minds of collectors and enthusiasts all over the world, including Robert O. Muller, Steve Jobs, and of course, Irwin Lavenberg.

To learn more about the art exhibition, “Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga: Changing Tastes in Japanese Woodblock Prints,” see here.

Exhibition Consultant: Lynn Katsumoto

View the Lavenberg Collection of Japanese Prints at myjapanesehanga.com